The pluralistic power model instead assumes that “power in society ultimately comes from the people: rulers only have that power which people provide to them.” This means activists must seek active popular support.

Erica Chenoweth, professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School, is referenced to support the claim that 3.5 per cent of the national population needs to be actively engaged in a campaign for it to guarantee significant social outcomes.

Engler, summarising, states that out of “300 nonviolent and violent campaigns worldwide from 1900 to 2006, none of the cases failed when they had achieved the active sustained participation of just 3.5 percent of the population – and some succeeded with far less than that.”

He adds: “Of course, 3.5 percent is nothing to sneeze at. In the United States, this constitutes over 11 million people.” Active Popular Support (APS) is therefore the core theory, grounded in the field of civil resistance, that explains how almost all social movements in modern history have worked. Engler also cites the work of Frances Fox Piven, a professor of political science and sociology, to claim that APS is the “reason why every major social movement in America won when it won”.

In 1987, Bill Moyer of the Social Movement Empowerment Project published The Movement Action Plan: A Strategic Framework Describing The Eight Stages of Successful Social Movements. He argued: “The central issue of social movements…is the struggle between the movement and the powerholders to win the hearts (sympathies), minds (public opinion), and active support of the great majority of the populace, which ultimately holds the power to either preserve the status quo or create change.”

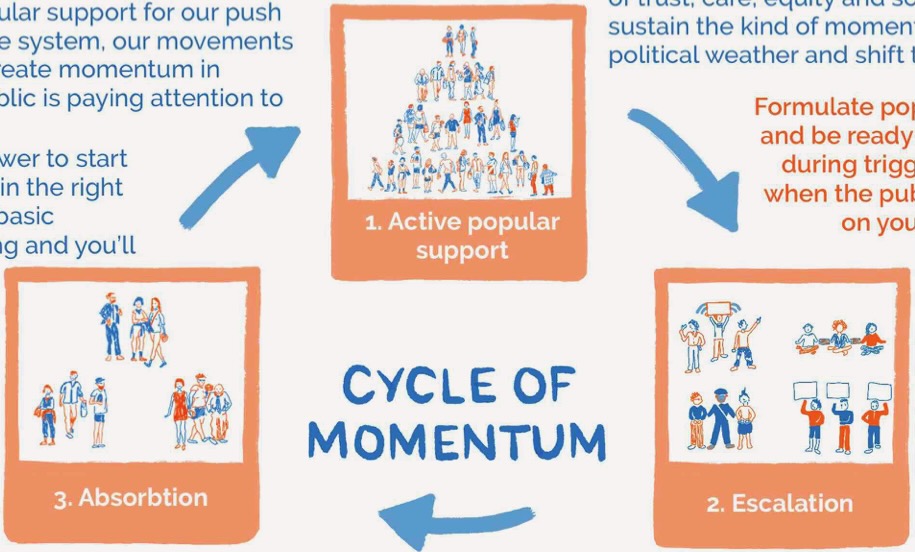

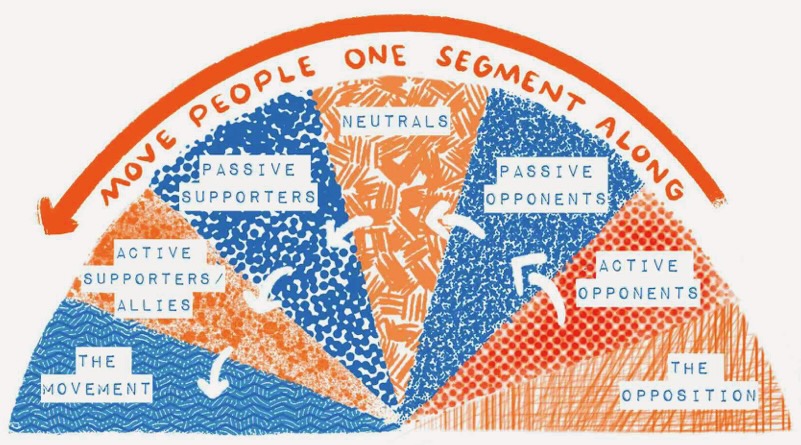

The development of active popular support for a specific campaign in turn relies on the successful deployment of three lower-level concepts: the spectrum of support, the pillars of support and the polarisation of support.

Spectrum of support

The hybrid approach does not simplify the elements of social change to three (us, lever, target) but instead identifies a “spectrum of support” for the desired outcome. This spectrum is divided into nine distinct colours (or three temperatures further subdivided into three hues): 1a. the movement; 1b. active allies; 1c. passive allies; 2a. friendly neutrals; 2b. neutrals; 2c. unfriendly neutrals; 3a. passive opposition; 3b. active opposition; 3c. core opposition. The aim of the activist is to move the population through the spectrum from opposition to movement affiliation. There is a “laser focus” on how members of each colour of the spectrum need to be engaged. Engler claims this is “how you win”.

The population are not simply characterised by their current relation to the campaign aim. Society contains institutions, cultures and less formal networks. The campaign therefore has to understand how the opposition – often the powerholders, the governments or corporations – maintain their power through such institutions.

Pillars of support

The people in power, specifically, rely on “pillars of support”, which are, of course, populated by ordinary people. The prime minister, chief executive officers, and even the military rely on the support of those they command or lead. These pillars are listed as the law, services, businesses, police and education. The members of each pillar can withdraw this support – and this must be understood by the campaign participants at every level. Engler states: “We’re really focused on pulling down the pillars of support, not the guy on top.”

This discussion is not a million miles away from the revolutionary theorist Antonio Gramsci’s still further complex discussion of how the hegemony of the ruling class gained through support of “parties” or complexes of human engagement such as institutions or social groups and the ability to create a “common sense” belief in the legitimacy or permanency of power. The aim of the movement is to gain the active support of as many people on the spectrum of public opinion as possible, with a specific focus on developing traction within the main pillars essential to ruling-class hegemony.

The ask presented to the public is determined by their current position on the spectrum of support. The public can be asked to vote, act, persuade, donate and act in non-cooperation with the status quo in order to support the movement in winning on its stated aims and objectives. The most obvious form of APS is voting, but further engagement in civil movements is necessary to achieve real change. The example given is that Richard Nixon, a conservative US president, formed the Environmental Protection Agency because of pressure from the public.

Once we understand that the population is internally differentiated in terms both of their existing attitudes to the campaign aim and of their current role in society, we need to have a clear conception of how we can move them – move them towards active membership of the organisation, and move them away from propping up the powerholders sustaining the status quo. We need, therefore, to understand polarisation.

Polarisation

The aim of the campaign according to the hybrid model is to polarise the public, to ask people to take a position within the spectrum of support and then also to move towards active support. The goal is to shift people towards increasing their support. This might seem obvious, but what differs in the hybrid model is an understanding that every action that wins support will also create some public opposition. “Most of the strategic debates is because people do not realise that we are running campaigns and we are picking demands because of the influence it has in polarising the public to us,” Engler concludes.

One of the most important arguments from Saavedra and Engler is that if the action secures more support and also more opposition as neutrals become active supporters or opponents, this is still a positive development for the campaign.

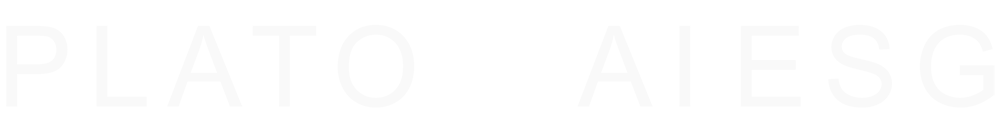

Polarisation in turn is created by a three-pronged feedback loop: the nonviolent action for a popular demand creates popular support, which creates a strong movement organisation, which can then mobilise a larger nonviolent action for a popular demand, ad infinitum.

Structure campaigns may influence a small, specific sector of society to lobby political leaders. The focus is often on instrumental protest, with real-world impact. This might include causing disruption that would be keenly felt by those leaders. However, the momentum and integration models are more concerned with gaining widespread popular support through more symbolic protests aimed at gaining attention, building the movement and “changing the climate”.

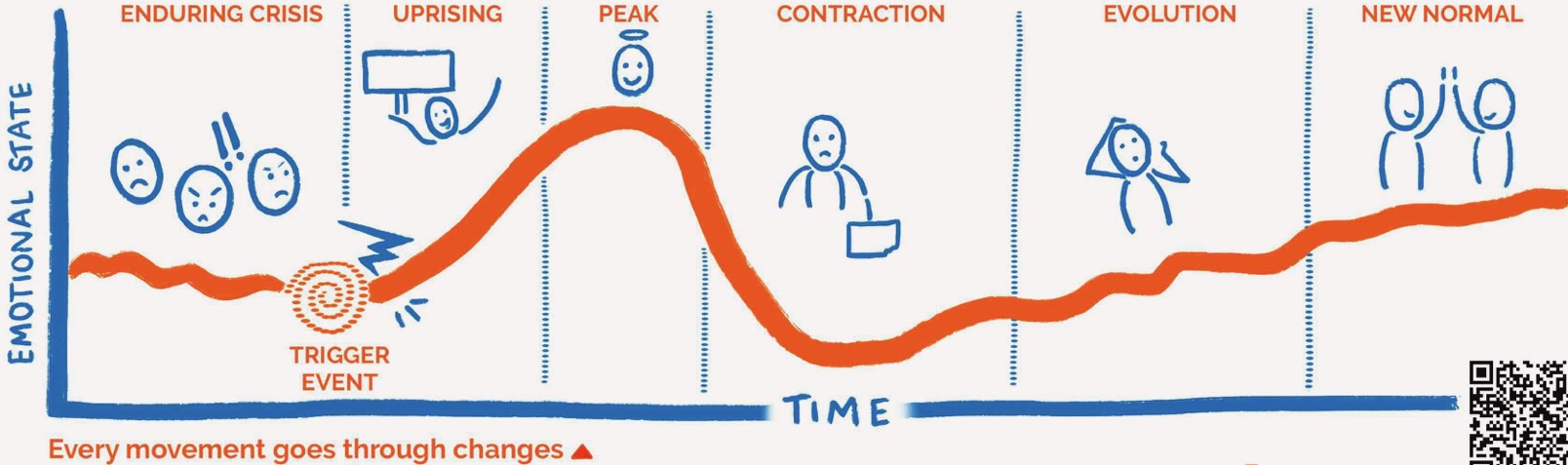

This determines the campaigns and tactics that are adopted. The cycle of momentum moves through popular support for the movement that feeds into strong movement organisation, which can deliver nonviolent action for a popular demand, through multiple cycles. The cycle moves through trigger events and moments of the whirlwind that each polarise the public, which in turn starts to undermine the pillars of support for the powerful. Engler claims: “When they no longer have the support, their power is diminished, and they have to concede to your demands.”

ESCALATION

Saavedra is quoted at the beginning of this article as saying: “We need to engage the whole public, we need to engage the masses, and if the masses do mass non-cooperation with the system in place then the rulers, the people on top, will not be able to deal with us.” He continues: “The most important aspect of gaining such support is escalation, which in turn creates momentum.”

The hybrid model promises to provide a small number of campaigners with the tools to deploy a campaign that will gain mass active popular support, and deliver substantial change. While it might seem obvious that any campaign needs to grow in size, and increase its membership and support, too few activists design this into their activity. The hybrid model offers a three-step process to escalation: the adoption of a popular demand, the deployment of trigger events, and the creation of moments of the whirlwind.

Popular demands

First, the choice of campaign and campaign ‘ask’ is decisive. Activists should not think about what seems achievable, modest, nor should it present a complex legislative solution to a problem identified by social scientists or specialist campaigners. Instead, the campaign needs to be ambitious, and should appeal to the public immediately.

The advice is not to target a specific political or corporate chief executive. Instead the movement should appeal to the general public by presenting a “popular demand”. The momentum approach seeks large social transformations even when “starting with issues that the community cares about, such as fixing the [street] lights.”

Trigger events

The second stage of escalation is the deployment of trigger events. This might include relatively small protests, but they are designed to polarise public opinion, to garner national news coverage, and most of all to light a beacon that will attract the first wave of supporters who will join the campaign.

Gene Sharp, the author of the three-volume opus The Politics of Nonviolent Action, collated precisely 198 methods of nonviolent action, any one of which can provide the inspiration for a specific event. These include, but are not limited to, picketing, flags and colours, haunting officials, vigils, political mourning, renouncing honours, student strikes, civil disobedience and even hunger strikes.

The aim is to design small actions that are difficult to police and are likely to attract the attention of the media and the public. A successful trigger event will be replicated by people not in the leadership, or indeed within the movement itself. “It creates a massive viral outbreak of the campaign.” The claim is that even small actions can work as trigger events. An example is just six people interrupting Obama, when he was US president, during a public speech.

A dilemma action is specifically designed to create “win–win” situations and, more importantly, put the opposition in a “lose–lose” situation. For example, campaigners for the DREAM Act encouraged migrants to donate blood, cutting against the public perception that migrants are a burden or drain on society in a very specific and emotive way. “For us the goal is to create trigger events and moments of the whirlwind that can polarise the shit out of the public,” Engler explains.

Trigger events can be externally created or spontaneous, rather than deliberately initiated by the movement itself, and these can be capitalised upon to create momentum. A key to success of a trigger event is media coverage. A series of trigger events can escalate to the point where “you get so much media, there is so much energy” that a whirlwind will evolve.

Historical examples of trigger events presented in the talk are: Gandhi making salt by the sea, leading to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which took place on 13 April 1919 during the fight for Indian independence; the D Day protests in Birmingham, Alabama, the Bloody Sunday police attack in Selma, Alabama in 1965 and the Martin Luther King, Jr. speech during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, during the US civil rights campaign; the free speech protesters at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois in 1968; the Clamshell Alliance protests that shut down a nuclear power plant at Seabrook, New Hampshire following the Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania in 1979.

The whirlwind

Nicholas von Hoffman was a grassroots activist during the Freedom Rides protests that began in the US in 1961. The riders were “groups of white and African American civil rights activists who participated in Freedom Rides, bus trips through the American South in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals”. The protests started small, but suddenly became national news, and then made history.

Von Hoffman had been organising meetings for months. “All of a sudden the church was packed.” He recognised a complete sea change in public attitudes and recognised that the protest organisers needed to change everything, to seize the opportunity. Engler states: “He went back to Saul Alinsky and said, ‘we need to rethink everything because we are in a moment of the whirlwind.’”

The term ‘moment of the whirlwind’ has now been adopted to describe the huge upswell in public support that can lift – and indeed overwhelm – a campaign. The whirlwind can be seen simply as a spontaneous moment, or an inflection in a historical process. However, the hybrid model holds out the promise that a moment of the whirlwind can be consciously and deliberately created by the campaigners themselves.

The ultimate aim, therefore, is to seed a series of trigger events, knowing that one of them will then result in a moment of the whirlwind. The organisers will not know beforehand which trigger event will take off, or go viral. Nonetheless, the deployment of a number of well designed trigger events certainly makes such a historical moment possible.

The successful uprisings against dictators around the world have also included trigger events that have been turned into moments of the whirlwind. The examples given include how a general strike was amplified into the downfall of the government in Serbia and other “colour revolutions“ and also the “day of rage” or “Friday of anger“, which took place in Egypt on Friday 28 January 2011.

Social movements have deliberately created moments of the whirlwind, rather than simply capturing significant events in history. “We have to ask how the hell are we going to do that?” The science of moments of the whirlwind is, Engler argues, “prophetic promotion”. “You need to have a vision that is beyond your capacity to build it: in Serbia that was a general strike to force an election.”

The Momentum Campaign organisers specifically advise that social movements “hype it up”. The momentum of any movement must be captured through the deployment of an activation plan that sets out a Big Vision. This echoes the activist advice that “if you build that vision, they will come.” The aim is to be the catalyst that allows others to come together, to have permission to manifest a massive event.

The undergirding belief is that the public will recognise injustice, and will take action, as soon as the seemingly impossible appears possible. The public is almost waiting at the station. The way to build a critical mass is to promise the public that at a certain time, and at a certain place, there will be a critical mass, a moment of the whirlwind. “The solution is the movement.”

ABSORPTION

Social movements sometimes fail precisely because they fail to gain popular support. However, some social movements fail even when, and perhaps because, they win popular support. The problem is, they are not ready for it. Indeed, they may actively resist it in order to maintain the power and prestige of the incumbent leadership, for example.

This can be seen in the case of the Stop the War movement in the UK, the Occupy Wall Street events in the UK and perhaps most recently with the mass protests against genocide in Gaza from October 2023. In each case, millions of people took to the streets, but the infrastructure was lacking or was not fit for purpose for translating these popular events into institutional structures that are both long-term and effective. The structure organisation can meet success with an existential crisis typified by inertia, infighting, and hostility to the public itself.

The hybrid model suggests that moments of the whirlwind will happen, usually spontaneously and often surprisingly. Therefore the campaign organisation must plan for this eventuality. It must have the infrastructure ready – the grand strategy, the trainers to deliver mass training, the culture – to absorb a new membership in a matter of weeks, if not days. This is captured by the question: ‘OK, we have a mass movement: what the heck do we do with all these people?’

Onboarding

The hybrid model is designed to deliver a “cycle of absorption”: the increase in popular support needs to be translated into organisation (the structure tradition), which in turn builds the next nonviolent direct action (NVDA) (the momentum tradition). The mass NVDA must then be translated back into popular support. Practically, emails need to be captured, commitments entered into, people recruited into the structure of the institution.

People need an easy way to get involved in the first place. For example, an activist calling for the DREAM Act to be adopted appeared on a Spanish TV show in 2010 wearing a t-shirt asking people to text ‘trail’ to a number and join after the Trail of Dreams demonstration from Florida to Washington DC. The public sent 5,000 texts with new phone numbers for the organisers to call. “Once you have their number, you can invite them to protests.”

A member of the public might visit the website after seeing a news story about an action and then take part in an online action, such as a petition; they will be encouraged to attend a real-life protest; they will be invited to a mass training; and finally they will be asked to join as a volunteer organiser and later form part of the leadership team. Absorption is not a linear process, and people might attend protests several times before becoming a volunteer.

The importance of absorption is emphasised through the success of the DREAM Movement in the US, where Saavedra took a leading role. The aim was to have long-term migrants to the US, often from Mexico and South America more generally, naturalised and given citizenship. Indeed, Saavedra learned the hard way about the need for absorption and a ladder of engagement.

A small group of people sent out a call to action, and to their surprise 400 students turned up and took part in the action. But without an absorption strategy, the organisers failed to translate this into a bigger organisation. This could have started with a simple task, such as collecting emails and phone numbers. “I didn’t even know what we were doing next – I didn’t have a plan for afterwards.”

Saavedra learned from this mistake. Before the next action a clear absorption strategy was developed. This began with simply collecting phone numbers from people when they came on a protest. The actions at the congress went from 40 attendees in 2010 to more than a hundred, and then several hundred in a few years.

Mass training

Perhaps the most important aspect of the ladder of engagement is mass training. This is where people become activists and understand the DNA and the strategy of the organisation. The training is delivered through a “voluntary organising structure”. Saavedra argues: “Mass training is the best thing you can do for absorbing momentum…training is one of the most important things for the integration and escalation into a stronger organisation.” He concludes: “There wouldn’t have been a DREAM movement if it was not for mass training.”

Marshall Ganz, often described as the architect of Obama’s field campaign in 2008, was an advocate of mass training. He argued that every volunteer could be funnelled through the mass training process. They were taught to use strategy, story and structure. And then sent out onto the streets to deploy that training. And it worked.

Saavedra and his fellow activists delivered training for more than 1,500 people. The leaders would go to a town, find 50 people, train them, form teams, and give them the DNA and the strategy for the next five months, and organising skills. The same mass training approach was used in 2010. In Arizona, the Obama campaign registered 34,000 new voters in one election cycle. “It was humongous.” In Florida, we went from 150 people to 2,000 people a couple of weeks later, in a place where we had no relationships. “It was insane.”

Structure organisations can often resist the implementation of mass training. “If you are constantly doing canvassing out on the streets, to do a mass training, it takes a lot of resources. To pull organisers out of the field, and do this big training,” Saavedra recalls. “People would tell you that makes no sense.”

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://theecologist.org/2024/apr/12/solution-movement