An Interview with Erin Zimmerman’); return false;” title=”Printer Friendly, PDF & Email”>

Science isn’t just for scientists. It’s for everyone. And species loss is everyone’s concern.

Introduction

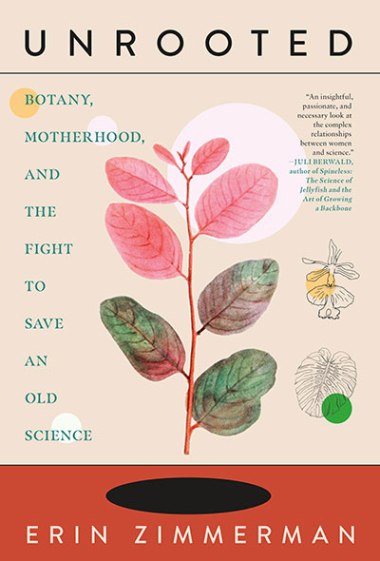

Science memoirs are gaining in popularity, with books like Hope Jahren’s Lab Girl and Cassandra Leah Quave’s The Plant Hunter. Erin Zimmerman, Ph.D. adds her own memoir to the collection with Unrooted: Botany, Motherhood, and the Fight to Save an Old Science (Melville House Press, April 2024). Zimmerman writes eloquently about the decline of botany and natural history in scientific research, as well as the challenges of becoming a mother in an environment that doesn’t really support that life decision. She combines interviews with well-known women botanists and illustrators with her own research into the history of botany and herbaria, telling a story that ends on a hopeful note with public participation in citizen science. Zimmerman’s book is a testament to the unknown paths our futures will take, from science to writing, and from singlehood to motherhood.

Zimmerman grew up in a farming region of southern Ontario, spending her summers as a teenager detasseling corn to make money to buy her first laptop. She received her Ph.D. from the Université de Montréal, where she studied the Dialiinae group of plants to understand their place on the botanical tree of life. She did a postdoctoral fellowship at the Université de Montréal’s Biodiversity Centre before turning to science writing. She has been published in The Cut, HuffPost, Narratively, and Undark, among others. She lives in a small town in southern Ontario with her husband and four children.

I spoke to her on an unseasonably warm spring afternoon in March.

Herbaria have a real image problem—well, natural history in general has an image problem. It looks old and irrelevant but it’s not.

Interview

Sarah Boon: I love the subtle humor in Unrooted, such as, “Floral development research is a great way to develop the skilled hands of a surgeon without having to be burdened by all that extra income.” Or, “I was happy not to have learned what it’s like to have a giant snake try to drown me in a swamp.” How do you think humor helps in telling your story?

Erin Zimmerman: I tried to keep the book fairly light—I mean, extinction, sexism, dealing with anxiety and motherhood: there’s a lot of heavy stuff there. I didn’t want this book to be a slog. My editing required dialing back some of my pessimism a little bit; I appreciate my editor having done that. I want it to be a fun read, I want the science to not be too heavy, and I want the heavy themes to not be too heavy.

Photo courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

Sarah Boon: Can you describe what it felt like to see an herbarium specimen collected by Charles Darwin when you were in the herbarium at Kew Gardens?

Erin Zimmerman: Oh, wow. I was in disbelief. I didn’t expect to be seeing famous names on the herbarium specimens per se. I was also new to it then—that was my first time touring an herbarium. For all of Darwin’s flaws, which I also get into a bit in the book, I looked up to him a lot, personally. Getting to see his actual work, his botanical work, was really inspiring and surprising. You really feel like you’re looking at history.

Sarah Boon: I appreciate how you navigate the awkwardness of Darwin’s views on women and people of color. I also like the irony of Darwin being the “poster boy for modern professionalized biology” even though he wasn’t a scientist. What are your thoughts on changing the names of species named for men who supported slavery, misogyny, and racism?

Erin Zimmerman: Oh, yes, that’s a big discussion right now, because of course, the American Ornithological Society recently decided to change all the common names of birds that were for anyone, not just problematic people. It’s something I’ve thought about a lot, because there are a lot of plants named for people. But it’s tricky because, for example, I wrote about Hendrik Uittien, the Dutch botanist, and about the species that’s named for him. He worked against the Nazis and helped people in his community during the occupation. He helped housewives use wild plants to feed themselves, you know? He was a hero. It’s hard to separate these two things. There are women whose only recognition for their work is that they got a plant named after them at some point. And I hate to see all those go. But then, of course, where do you draw the line? I’d like to see it done on a case by case basis, so we don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater, but I also do recognize that it’s slippery to say, well, this person is rotten enough that we get rid of the plant named after them, and this person isn’t. I’d like to see it be an ongoing discussion. I don’t necessarily want to see all the names go.

Sarah Boon: I really enjoyed that story in the book about the war hero Hendrik Uittien, described above, and the species named after him. How do you find these kinds of stories?

Erin Zimmerman: I lucked into a few; they’re sometimes written into the original description of the plant, so when they’re named the original author will often talk about where the name came from. During my doctoral studies I did a fair bit of going back and digging up the original taxonomic descriptions of these plants to compare against the herbarium specimens that I was studying, to see if they’d seen anything that I didn’t, or vice versa. I saw a lot of the original descriptions, and it’s fun because there are little stories tucked in there. His stuck with me because he was not well known outside of Holland. I spoke to his biographer, a Dutch writer (the biography’s in Dutch, so I couldn’t read it). But his biographer was nice enough to fact check what I wrote about Uittien. And this writer was so happy that anyone outside of Holland was even paying attention and writing about him at all. That’s why I felt a bit bad that the species probably won’t stand because of changes in taxonomic classification. The name will be there somewhere, but it likely wouldn’t stand as the official name.

Sarah Boon: You write candidly about your emotions: the competition with other students in the lab, the impostor syndrome, the perfectionism, the feeling of self-righteousness when one of the women you were working with left the lab to have a baby. What was it like to interrogate your emotions like that? It couldn’t have been very comfortable.

Sarah Boon: You write candidly about your emotions: the competition with other students in the lab, the impostor syndrome, the perfectionism, the feeling of self-righteousness when one of the women you were working with left the lab to have a baby. What was it like to interrogate your emotions like that? It couldn’t have been very comfortable.

Erin Zimmerman: It was not. The woman in the lab, thankfully, is a very kind and understanding person who knows what I wrote. She’s not read it. But she’s aware. I think it’s important to be honest; I would like to think that there will be some readers of this book who are in similar positions. I would like to think some women in science will read this book, and see themselves and maybe feel that what they’re experiencing is normal. There was a part that did not end up being included in the book: with each interview I had with one of these senior female scientists, and I asked them what they thought of being a woman in botany and how it had changed over the course of their careers, because they’re all later in their career. It came up more than once that there was a certain amount of competition between women that the environment forced, but that also got in the way of being supportive of one another, and I think I was no different. So I think it was important to cop to that. I do think imposter syndrome is something that, thankfully, we’re a lot more aware of. You hear it discussed regularly.

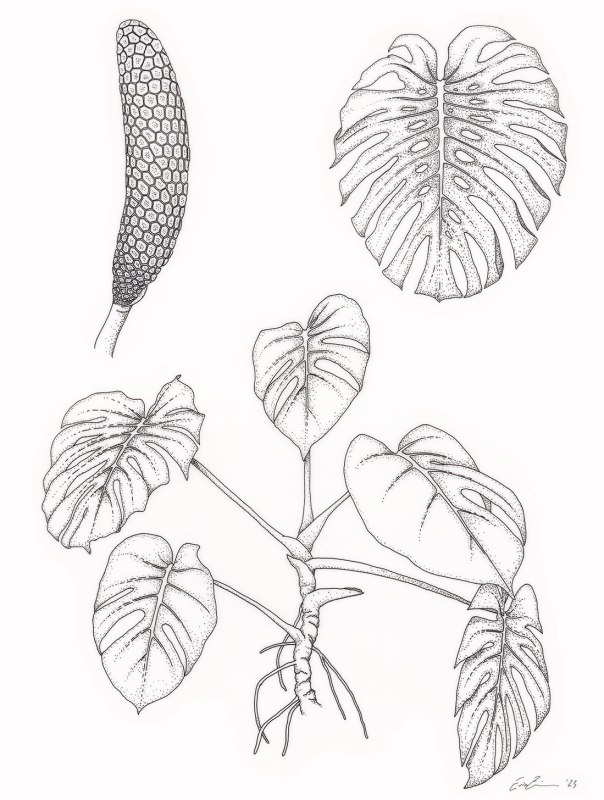

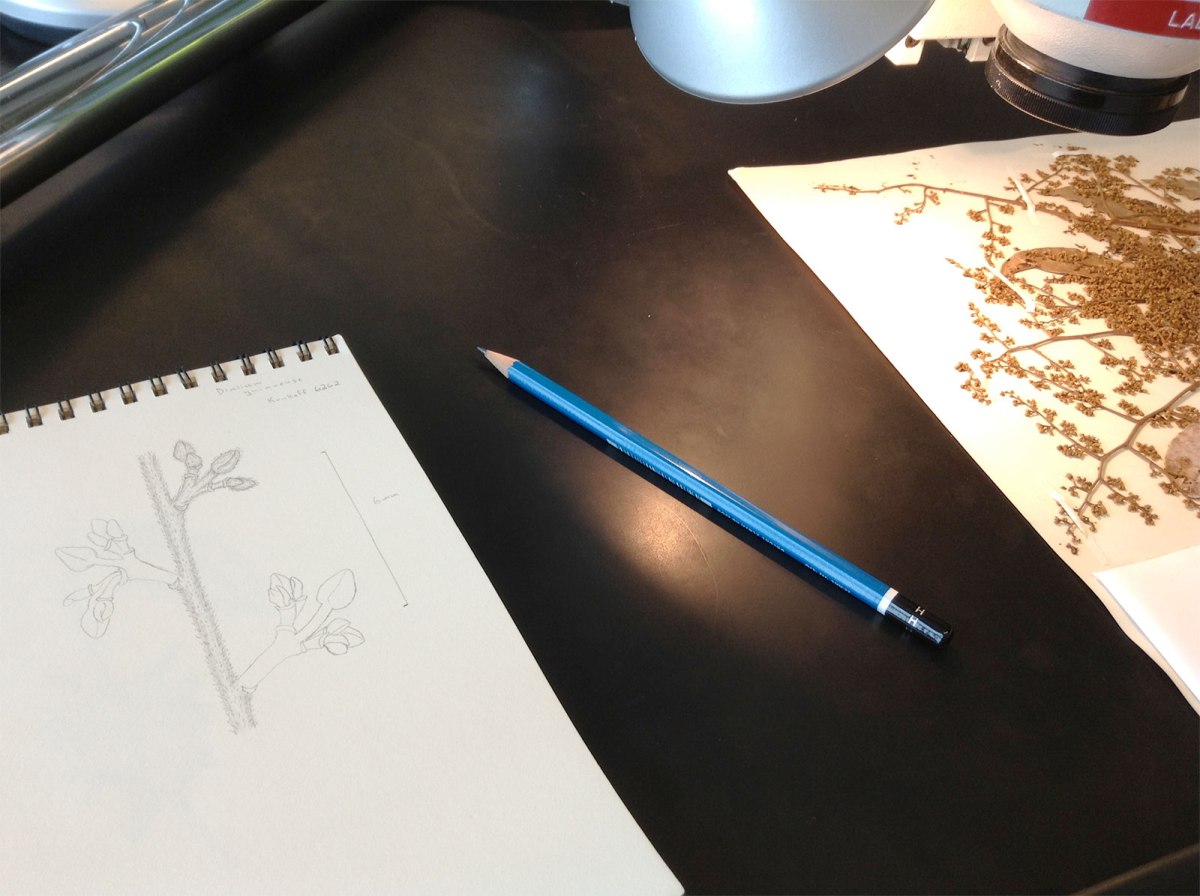

Sarah Boon: You did all the illustrations for your book. What was that like? Was it calming and meditative, like when you did the illustrations for your Ph.D. dissertation?

Erin Zimmerman: Yes, it was. I discovered audiobooks while I was doing that. And I got through more books while I was illustrating than I have in some time, because I’m a very slow reader. But oh boy, just getting to fall into my work and listen to a book while I was doing it was wonderful. I really enjoyed that. And it’s a nice change from writing too, because you can use different skills for a while. That’s a nice shift.

Illustration by Erin Zimmerman

Sarah Boon: Do you see your illustrations as art? I know whether it was art or science was a discussion you had with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History botanical illustrator Alice Tangerini.

Erin Zimmerman: Alice actually felt that illustrations could attain the level of being art if they appealed to a wide enough audience. Personally, I feel illustration is the better word for what I’m doing. I don’t feel like I’m creating art. For her it was about the audience who appreciated her work. For me, I feel like art is a big word, and it’s intimidating. So illustration feels good.

Sarah Boon: Having children isn’t just difficult to juggle for women in science—it can be a challenge as a freelance writer, as well. I would argue that it’s more difficult because you work from home, so are seen as “not doing anything important.” How did you manage to write your book with four children, some of whom were often home sick?

Erin Zimmerman: It’s tough because my whole freelance career I’ve had to take on less than I would like to because childcare is unpredictable. It remains that way even now. My day one strategy was always putting things in easy, bite-sized chunks that I could work on. And part of that too was just that my twins were very young when I was writing most of this book and I was just exhausted, so it has to be easy. I did this sort of big, upfront investment of time to break the whole thing down and make it easy. Some of the book I wrote with my thumb on my phone while holding a baby. You learn to work during naps, or when someone’s amused for 20 minutes in front of the TV, or you take them out for a walk and let them play in the park and I’m back on my phone, thumb typing again.

It is really important to me to be present with my kids: if they’re with me and awake, I try to be present. But you can steal moments here or there that don’t have an impact on them to get that work done. That’s it. It’s hard. It’s all very unpredictable. I mean, just this past January, I lost half of my working days in a month because of kids being home sick. Ultimately, I will have done less to promote the book, for example, because that happened; over the course of my career, I will have taken on less because I’m always conservative about what I can manage. It comes with the territory.

Specimen collections and natural history research are not some obsolete Victorian holdover, but a crucial and ever-evolving resource for knowing our planet and protecting its biodiversity.

Sarah Boon: You write that “part of supporting science is supporting the people who do it.” If your postdoctoral supervisor and lab mates had been more supportive of your pregnancy and then your daughter, would you have stayed in academia? Or did you already feel it wasn’t for you?

Erin Zimmerman: I think I would have stayed longer. One thing I discuss is a certain amount of disillusionment at the entire structure of postdocing, and the life sciences have the longest average terms of postdoc, after you get your Ph.D. but before you get to a permanent job. You’re potentially looking at spending a lot of your 30s as a postdoc. And it’s questionable whether I’d have been able to do the type of work I was doing in my Ph.D., though again, not impossible.

Another issue that I discussed in the book is what I call the two-body problem. This is a phrase you hear in science from time to time, where two people who are married or in a long-term partnership are trying to make their careers work. By the time I was a postdoc, I had to stick to a particular location. You get married to someone who has a job in a particular place, and you need to stop and put down roots and build a life there and you have a child. It all just becomes more difficult to be as nomadic as academia will force you to be. I definitely think I would have stayed around longer and tried to make it work more had I not struggled so much at that very vulnerable time. But I would have left eventually because of those problems in total.

Sarah Boon: You mention that we’re losing the expertise in botany to pass on to the next generation of scientists. What do you imagine botany will look like in the next 20 years or so, when there’s no one to teach natural history to students, or to identify plant species? Is there a way to stem the tide of knowledge lost by not funding morphology, taxonomy, and ontogeny research?

Erin Zimmerman: One of the programs I discussed was funded by the National Science Foundation in the U.S. specifically for knowledge transfer, from older scientists nearing retirement to younger scientists who were interested in taxonomy. Unfortunately it does not exist anymore. Looking at my own research, the reason I got to do what I was doing is partly because I was working on morphology, I was working with herbarium specimens. It was very observational and natural history-based, and molecular work as well. But I was able to do that type of work because I was safe under the umbrella of my advisor’s funding, which allowed me more freedom than I had once I was no longer a student.

I want to be optimistic and say we’re going to start to pull back from the brink. In the book I discuss how, at my undergraduate university, they closed the botany department while I was there and plant science was basically gone—not entirely, but it was not what it had been. Organismal research like what we talk about with natural history wasn’t really happening anymore. Some years later, I read a report that they established a biodiversity program in part to address that lack. I think the focus on addressing species extinction, that framing, really helps, because it’s not just a dried plant collection—it stops species from going extinct. That’s an easier call to action than trying to sell natural history. One of my interviewees mentioned that she is able to do a certain amount of morphology within her funding because she’s tried to tie it into research of the moment, something that fits with trends in funding. As long as she can keep her research tied to something that funders currently feel to be urgent and relevant, she can do the morphology work. I think this is going to work the same way.

Sarah Boon: There’s a drive to close herbaria, or move or split them up and send them to different herbaria, like what’s happening to the herbarium at Duke University. Wouldn’t it be important to keep the herbaria because you can extract DNA or other things from the plants?

Erin Zimmerman: In a lot of cases you can—not across the board, because some of them are just too old and degraded, but we’re getting better and better at that. One point botanist Barbara Thiers made when I interviewed her was that the total number of herbaria remains relatively steady, but that masks the fact that there are smaller ones being created but there are big, old, important herbaria being closed down. If you were to look at absolute numbers you might not see the problem, but an herbarium like Duke with close to a million specimens that’s been around for over a century is different than something new that’s just established. We’re getting better and better at pulling information out of them, and you just don’t know what in the future might be important and what you might able to do with them. There are things we’re doing now with herbarium specimens that half a century ago would have been unimaginable—like machine learning and artificial intelligence, and even how good at extracting and sequencing old and degraded DNA we are. These samples only become more valuable with time. Herbaria have a real image problem—well, natural history in general has an image problem. It looks old and irrelevant but it’s not.

Illustration by Erin Zimmerman.

Sarah Boon: What made you decide to end Unrooted on a citizen science note?

Erin Zimmerman: I wanted to end on a hopeful, encouraging note that was useful for readers because most of the people reading this book aren’t scientists and aren’t involved in the sort of work I am talking about. I want people to know that if you care you really can be involved. Natural history is special that way, versus the higher-tech experimental science field. You can do a lot by observing, by going out into the world and using something like iNaturalist to note where different species occur. Or it could be something like I tried at the New York Botanical Garden, where you’re doing transcription of century-old herbarium labels so you just need to be able to read cursive. It’s so approachable; you can learn through doing it but you don’t need any prior experience. I’d like people to be aware that they can be involved in something they care about. I wanted to end on a useful note.

Sarah Boon: I wonder if a lot of natural history isn’t happening in universities but has been offloaded onto citizen scientists.

Erin Zimmerman: I don’t want to see the justification being used that, “Oh, this is something that we can just get people at home to do.” Something I tried to emphasize in the book is that the expertise will always be needed. Citizen science is really helpful for data gathering but then you need people later down the pipeline to analyze that data. It’s got to be both. And it’s the same with machine learning. You don’t ever want to see that used to justify not having taxonomists because it’s not solving the problem in that way, it’s just easing a burden on the taxonomists that are there.

Sarah Boon: What do you want readers to take away from your book?

Erin Zimmerman: I hope readers will see that specimen collections and natural history research are not some obsolete Victorian holdover, but a crucial and ever-evolving resource for knowing our planet and protecting its biodiversity. I also want readers to understand that there is an avenue—many avenues, in fact—for them to be personally involved, in the form of citizen science. Science isn’t just for scientists. It’s for everyone. And species loss is everyone’s concern. For readers who have experienced the seeming impossibility of being mothers while meeting the demands of an unaccommodating professional career, I want them to see that they’re far from alone in that struggle, and it isn’t their fault if they ultimately decide that it’s best to walk away. It’s okay to look for another way to achieve your goals while meeting your needs and those of your family.

Sarah Boon: What are you working on next?

Erin Zimmerman: I want to keep writing about plants. But I’m also considering a project that isn’t plants. They say write about what you can’t stop thinking about, and I’m very fascinated with memory and the way our life is made of memories that can slip away so easily. My first major freelance piece for New York Magazine was on childhood amnesia, the way we lose those memories. And that is something I can’t stop thinking about, though I wrote it seven years ago. So I’m considering a temporary diversion to another topic. But ultimately I want to keep writing about plants.

Learn more about Erin Zimmerman on her website.

Sarah Boon has been published in Aeon, LitHub, Los Angeles Review of Books, Undark, Orion, and other outlets. Her science memoir, Meltdown: The Making and Breaking of a Field Scientist, will be published by the University of Alberta Press in spring 2025.

Sarah Boon has been published in Aeon, LitHub, Los Angeles Review of Books, Undark, Orion, and other outlets. Her science memoir, Meltdown: The Making and Breaking of a Field Scientist, will be published by the University of Alberta Press in spring 2025.

Read other interviews by Sarah Boon in Terrain.org: “Becoming Kin: An Interview with Gavin Van Horn” and “Biomimicry, Loss, and Building Community: An Interview with Margo Farnsworth.”

Header photo by tabaca, courtesy Shutterstock.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.terrain.org/2024/interviews/erin-zimmerman/